It happened on October 6, 1993. David Aldridge of The Athletic remembers it as one of the great upheavals in the history of the sport. Michael Jordan, a 30-year-old athlete in his prime, hung up his boots after nine seasons of exceptional performance in the NBA, with three titles in his bag and the memory of the high level exhibited in his last finals series, against the Phoenix Suns. The reasons? I had stopped enjoying the game. As Jordan Greer explains in the Sporting News, that October afternoon Jordan sat down "in front of a horde of shocked reporters" to tell them that professional basketball was so demanding that it simply wasn't possible to take it on without proper motivation.

Besides, I couldn't stand the fame. It was insufferable for him to feel adored, to have no privacy, to be forced to devote a substantial part of his leisure time to posing with fans or signing autographs. Jordan took questions and conducted himself with the press, drawing on the "charisma, level-headedness, sense of humor and occasional outbursts of anger, arrogance and pettiness" to which he had become accustomed. With tears in his eyes, he said he was proud that his father had been able to witness his last game live. In that appearance, Jordan slipped for the first time a detail that at the time was not taken entirely seriously: he was looking for new sporting challenges and was considering debuting in the major leagues of baseball, the sport he had practiced as a child, at the instigation of his father, before ending up opting for basketball.

Learn more

"They call me coronavirus": the nightmare of the Asian player who dared to be an NBA star

The Bulls were forced to reorganize in an accelerated manner shortly before the start of their first season without Jordan. The team seemed to be heading for a long journey through the desert, but the sudden defection of the soloist activated the rest of the orchestra. Under the "democratic" leadership of Scottie Pippen (who, only today, loathed Jordan for his crushing leadership, his suspicions, and his outbursts) the Bulls flourished against all odds.

A 21-year-old Michael Jordan in this image taken in 1983 stretches during workouts. Bettmann (Bettmann Archive)

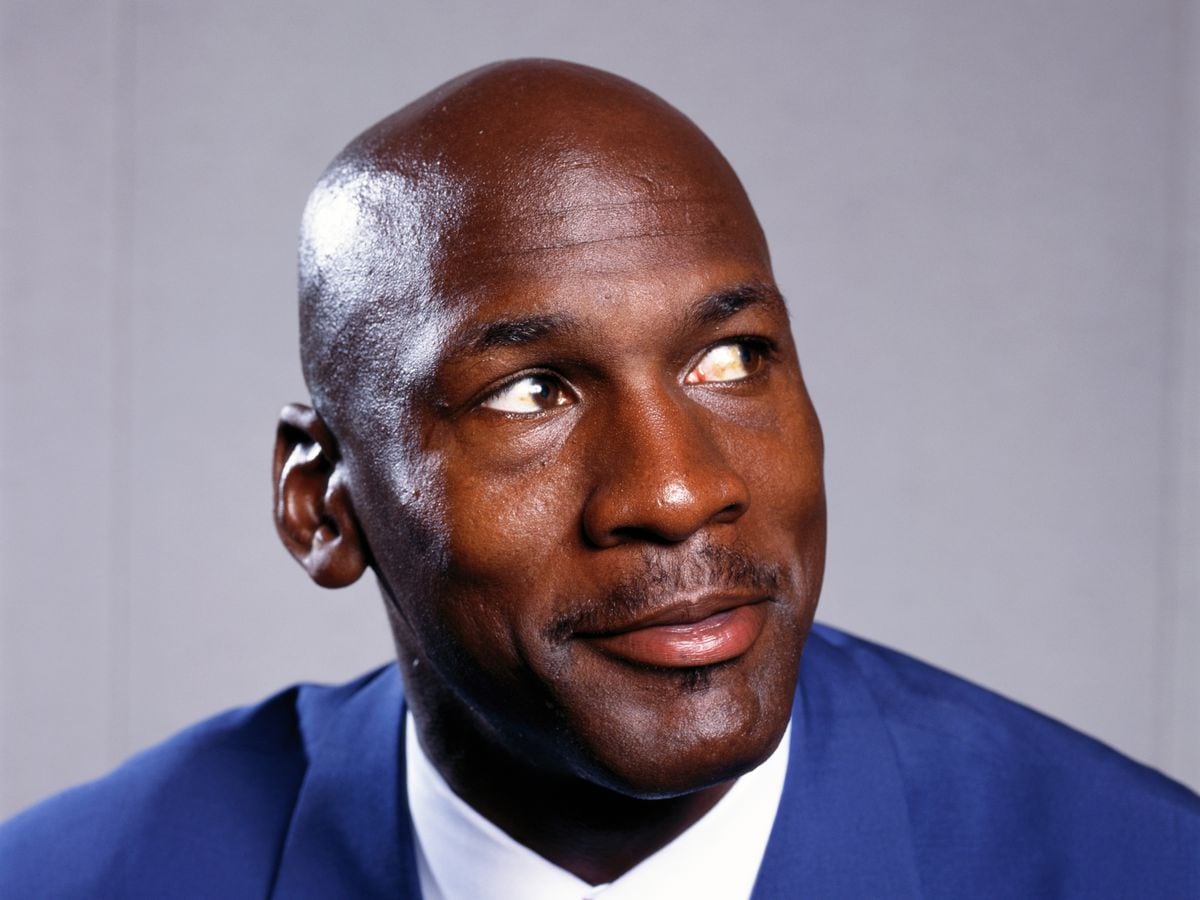

Michael Jordan during the ceremony held in Chicago in 1993 to celebrate his farewell to basketball. EUGENE GARCIA (AFP via Getty Images)

While all this was happening in Chicago, the defector, Greer explains, was beginning to realize that life away from the top was not as idyllic as he had imagined. In April 1994, in a now legendary interview with Ira Berkow of The New York Times, Jordan acknowledged for the first time that he missed the high-level sport. He was training with the Birmingham Barons, the Chicago White Sox's affiliate in one of baseball's minor leagues, and he had already assumed that his exceptional ability to play basketball might not be entirely extrapolated to other sports.

"Man, I think we've killed Michael Jordan's father."

"For years, I had the world at my feet. Now I'm just a 30-year-old meritorious man trying to make his way, with modesty, in a professional competition that he still doesn't know if it's too big for him." His Southern League debut had been so disappointing that, according to the Barons' coaching staff, he agreed to continue training without competing until he was "truly ready". But that moment didn't come. The interview with Berkow, moreover, was the first unmistakable symptom that Jordan had not been entirely truthful about the real reasons for his retirement from the NBA six months earlier.

Jordan, in fact, had suffered from severe undiagnosed depression since his father's death in July 1993. He didn't even have time to process the duel: he had just been crowned champion for the third time and had multiple publicity commitments that he didn't want to postpone. James Jordan Sr. was killed as he slept in his car at a rest area in Lumberton, North Carolina, after a long day of golf. He was 56. Two teenagers, Daniel Green and Larry Martin Demery, shot him to steal the brand-new $400,50 Lexus SC000 that his son Michael had just given him.

The grave of James Jordan, the father of Michael Jordan, murdered by two young men who subsequently stole his car. Chicago Tribune (Tribune News Service via Getty I)

Michael Jordan during a break from a game with the Chicago White Sox in 1994, when he left basketball for baseball. Focus On Sport (Getty Images)

At the wheel of the vehicle, the killers drove to a swampy area where they dumped the body. As they went through the deceased's documentation, Demery was the first to notice something they found unsettling: "Man, I think we've killed Michael Jordan's father." The homicidal duo was located shortly after, after making a series of calls with the victim's phone.

In his interview at the Barons' training camp, Jordan confessed to Berkow that trying his hand at baseball was nothing more than a posthumous tribute to his father: "It was his favorite sport. When I was a kid and we lived in Wilmington, we spent countless hours together in our backyard, practicing with the bat and gloves." Michael alternated between the two sports until he was 17 years old, although around the age of 14, when he became the starting forward for his high school team, Emsley A. Laney in Wilmington, it had become clear that basketball was his thing.

In 1990, according to Jordan himself, his father, sensing that he was going through a crisis of motivation, suggested that he follow the example of a pair of legendary athletes, Bo Jackson and Deion Sanders, and play two professional sports at the same time. That project didn't look realistic to Michael: he had a four-year contract with the Bulls, was collecting a multimillion-dollar salary, and was expected to make his team champion. But he took note of the gist: His father, the most influential person in his life, still wanted him to play baseball.

When that old dream finally came true, but turned into a frustrating nightmare, Jordan persevered, he explained, by resorting to mental dialogues with his father: "He tells me to keep trying. It doesn't matter what the press or the fans think. To be made fun of, to think that what I'm trying to do is ridiculous, it's part of the game. I don't have to prove anything to them. This is something between me and my father."

Michael Jordan during the press conference in Chicago in October 1993 in which he surprised the whole world by announcing that he was retiring from basketball. Ralf-Finn Hestoft (Corbis via Getty Images)

Jordan was able to persevere thanks to the generosity (or keen business sense) of Jerry Reinsdorf, owner of both the Bulls and White Sox. When Jordan sat down with Reinsdorf, a few days before his October 93 press conference, to thank him for his trust and announce that he was leaving the NBA, the mogul offered him the possibility of joining the White Sox while keeping the salary agreed with the Bulls.

While Reinsdorf thought it unlikely that Jordan would end up becoming a superstar at bat, he thought it was a good deal to keep him on the payroll while he remained not only the most famous athlete but the most celebrated person on the planet. Eddie Einhorn, one of Reinsdorf's main partners, agreed with the decision, which was ruinous from an economic point of view. Einhorn had a theory that Jordan was imposing a kind of irrational penance on himself for the death of his father, whom he felt he hadn't cried enough: "It will pass. He'll play basketball again. And when he does, we'll be there, waiting for him."

Play along gentlemen, the world is on the table

CBS Sports' Sam Quinn points out that there was another, even more uncomfortable reason for Jordan's erratic behavior in that crucial 1993. The player had developed a gambling addiction that had been brewing since his high school years and had become a real problem. He himself confirmed this in the sixth chapter of his documentary series The Last Dance.

Already in his years at the University of North Carolina, Jordan got into the habit of betting much of his mother's money on games of pool or darts. Later, having become the highest-paid athlete on the planet, he began to gamble "obscene" amounts in poker games with journalists from his circle such as Sam Smith or Lacy Banks. He embarked on multiple bets with the Bulls' security personnel, front office members and even teammates and members of the coaching staff.

Michael Jordan after substituting the ball for the bat in the fall of 1993.EUGENE GARCIA (AFP via Getty Images)

Pippen recalled years later that the best way to ingratiate himself with Jordan, a man with personal charm but a difficult character, was to gamble with him and, if possible, lose, because Jordan loved to have debtors, but he hated debt. The addiction to gambling accompanied him until the end of his career (Quinn claims that, already in 2001, he "ruined" the teenage rookie Kwame Brown in his time with the Washington Wizards, to the point that the boy's parents approached the club to intercede for him before an inflexible Jordan, who intended to charge him every last penny), But everything indicates that he reached his peak around that fateful 1993 in which almost everything in his life fell apart.

In February, the basketball player had to testify in a trial against drug dealer James Silm Bowler, in whose possession a $57,000 check with Jordan's signature was found. Michael acknowledged to the judge that it was a payment of a gambling debt. Two months later, in May, a sports journalist, Richard Esquinas, published a book about his own gambling addiction in which he claimed that he and Jordan had been playing golf together for several years and betting increasingly substantial amounts. According to Esquinas' account, the Chicago Bulls' No. 23 had owed him more than $<> million and was reluctant to pay them. I wanted to double down.

Jordan claimed that this was nothing more than hoaxes spread by an opportunist with a desire for notoriety, but he ended up reaching a private agreement to pay $300,000 to Encinas and thus cancel the debt. At the time, it was rumored that the mysterious injury that kept Michael away from the courts shortly before the start of the playoffs had actually been a covert sanction concocted by the NBA's high commissioner, David Silver, who wanted to give him a wake-up call, but without damaging his image.

A sequel that surpassed the original

The end of the story is well known. The promising Bulls of the best Pippen were not able to become champions in their first season without Jordan. They competed to the limit but were beaten by Patrick Ewing's New York Knicks in an agonizing Eastern Conference semifinal.

The following season saw an alarming decline in his performance and rumors began to swirl that Jerry Reinsdorf was trying to convince Jordan to abandon once and for all his absurd dream of making it in baseball and his talks with his dead father to return to the team and pull him out of the hole. The news everyone was waiting for came in May 1995. Jordan released a terse statement, a work of sports marketing art: "I'm back."

He put himself under his former skipper, Phil Jackson, and conducted the rest of the season with a disconcerting humility, respecting even the new hierarchies that had been consolidated in the team, praising "the professionalism and commitment" of Scottie Pippen and the "enormous talent" of Toni Kukoc. That season the flute did not sound. An in-form Jordan wasn't enough to regain positive momentum. The team fell again in the second round of the playoffs, this time to the glittering Orlando Magic in which a Bulls veteran, Horace Grant, had found a home.

But Jordan returned to work in the 1995-96 season. He stripped off the disguise of a false humble, regained his voracity and killer instinct, put the entire team, including Pippen and Kukoc, back into his service. Thus began his iron years, in which he won three more titles and established himself as the best athlete of the <>th century with the permission of Muhammad Ali.

The Brazilian national football team could not be world champions without Pelé in 1974 and Pippen's Bulls could not, in 1994, climb Everest without taking Michael Jordan on their rope. They did enjoy shortly after, to the immense luck of those added to the sport, a splendid Jordan after Jordan. After gambling addiction, simmering depression, baseball, humbling cures, and the voices of the dead father echoing in his head, Jordan was back to being the best version of Jordan. And Pippen continued to add to his trophy cabinet. Even if he was paying a cruel toll: to take on again the role of eternal squire of the man he detested.

You can follow ICON on Facebook, X, Instagram, or subscribe to the Newsletter here .